While there are plenty of paeans on what Amurika *is*—the City upon a Hill, The Great Experiment, a Melting Pot, the Global Police Officer, and so on—a nation cannot function without its administrative state. At the moment when that administrative state is fully encircled and infiltrated by oligarchic actors that threaten to usurp the powers inherent in the state, the nation itself is at great risk.

The relationship between the administrative state and a nation’s survival exists in precarious balance. While administrative institutions provide essential continuity and capacity-to-act that strengthens state resilience against complex challenges, this relationship becomes severely compromised when oligarchic interests capture these same institutions. The administrative apparatus ideally serves as both operational backbone and democratic counterweight to concentrated power, but cannot fulfill either function when redirected toward private gain rather than public purpose. This slide towards a fully parasitic oligarchy has been underway in some form for the duration of the nation, but following the demise of any guardrails on money in elections, the process, as it nears completion, threatens the fundamental viability of the nation.

When administrative bodies become extensions of oligarchic influence, a terminal cascade begins: public trust erodes as citizens perceive state unresponsiveness, inequality intensifies through biased resource allocation, and state autonomy weakens as decision-making becomes constrained by elite preferences. This capture undermines the fundamental legitimacy that allows nation-states to persist through crises and transitions. The survival of the nation-state thus depends significantly on maintaining administrative institutions that are sufficiently autonomous from both political volatility and oligarchic capture—a challenge that grows increasingly difficult in an era of transnational pressures, vast income inequality, and concentrated economic power.

Looking at the relationship between the administrative state, oligarchic influence, and nation-state survival in the contemporary United States reveals several concerning patterns:

The US is experiencing significant tension between its administrative institutions and democratic legitimacy. Federal agencies face challenges from both increasing political polarization and economic concentration. Regulatory bodies like the SEC, EPA, and FCC operate in an environment where industry influence through lobbying, revolving door employment, and campaign finance creates persistent, creeping risks of capture. This dynamic has contributed to public perception that government serves elite interests rather than any common welfare.

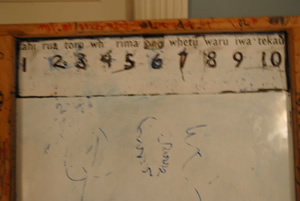

The administrative state’s credibility has been further stressed by political attacks characterizing it as an unelected “deep state” disconnected from democratic accountability. This narrative, combined with real instances of special interest influence, has accelerated erosion of institutional trust. Recent polling shows historically low confidence in government institutions among Americans across the political spectrum. This development considered in light of the fact that very few Amurikans even know what services many departments of the Executive Branch perform. Or what the three branches of the Federal government are to begin with. This measure of trust deficit is a fundamental challenge to state legitimacy and stability, as is the lack of fundamental education in civics. There is much evidence that the administrative apparatus is struggling to maintain both technical competence and perceived democratic responsiveness in a polarized environment where economic power is increasingly concentrated among a tiny group of individuals and corporate entities.

From a Confucian perspective, the remedy to such administrative capture lies not primarily in structural reforms but in moral revitalization. Confucian philosophy would interpret oligarchic interference as a symptom of ethical decay among both governing elites and society. The solution requires cultivating virtuous leadership (junzi) that views its position as a sacred trust rather than an opportunity for personal gain. Administrative officials must recommit to proper ritual conduct (li) that reinforces their obligations to serve the people rather than private interests (i.e., a demonstrated deference to the Constitution and to its moral framework, *not* obeisance to Dear Leader). This approach emphasizes that effective governance emerges not merely from institutional design but from the moral character of those who serve within institutions. Thus, the Confucian response would prioritize ethical self-cultivation among administrators and leaders, creating a moral ecology where serving the public good becomes internalized as the highest virtue, thereby restoring the proper relationship between state and society that sustains national cohesion and legitimacy.

The current Amurikan administration is clearly demonstrating an advanced state of acute moral decay. This is not a new development, but a culmination of a number of structurally-determined processes. Is there any possibility of wide-spread moral ‘recovery’? Perhaps, but it is crystal clear that the so-called leaders of the government are largely in the grip of a deeply corrupt fever of influence and power ruled by Machiavellian struggle and a blatant lust for power. Those who tear the administrative state down instead of examining their own hearts for moral clarity will be guilty—with little chance for redemption—both of the destruction of Self, but also the widespread destruction of stability and safety for millions of Others.