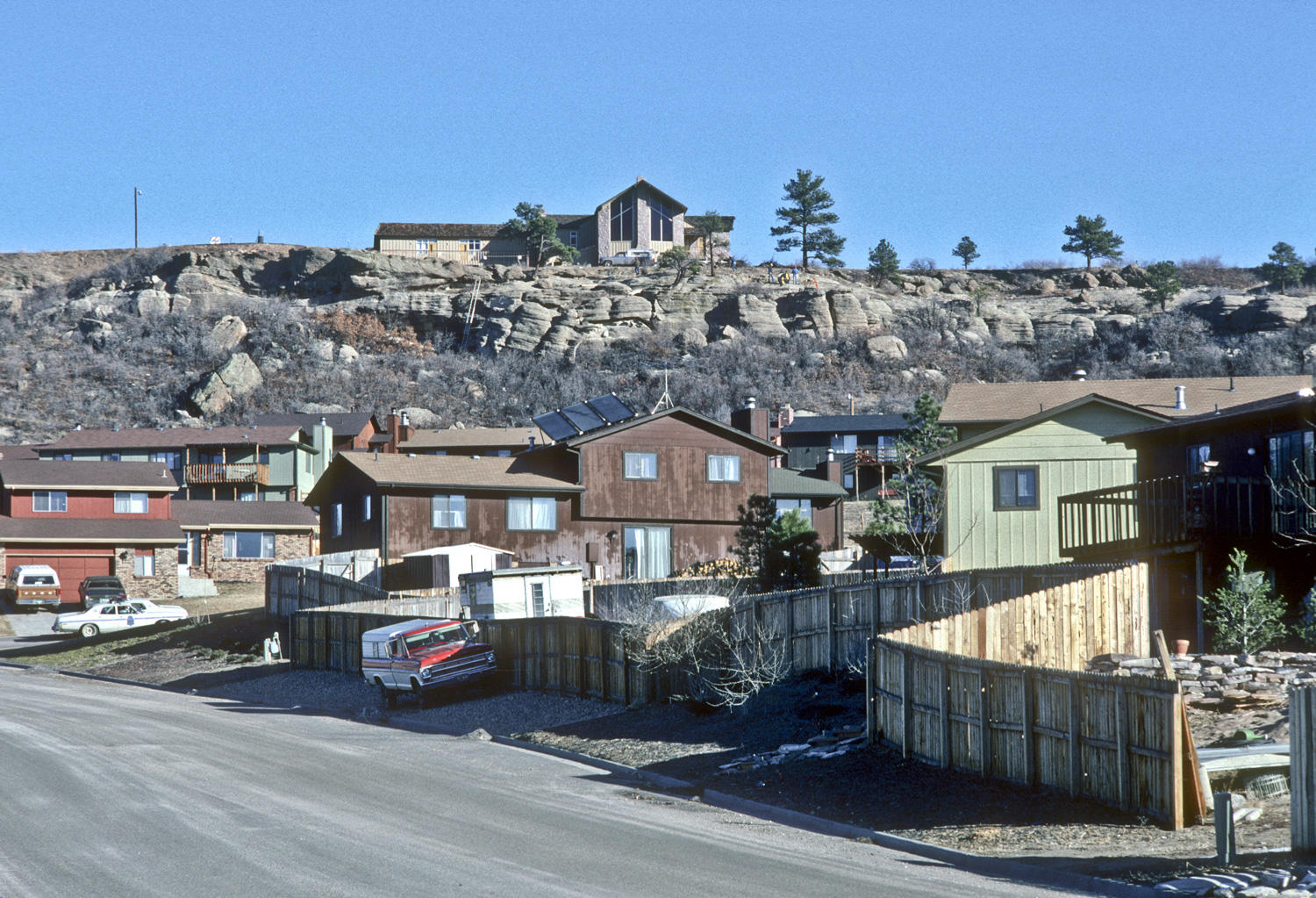

The state geological survey was brought in to examine the site of St. Francis of Assisi Church in Castle Rock, Colorado after a block of sandstone detached from a cliff face on their property in January 1981. The block presented a risk to homes at the base of the slope south of the church property, and was subsequently broken up using passive demolition methods. Other detached blocks continued to present a rockfall hazard to six homes located at the base of the bluff. No consideration was made to address rockfall hazards at the base of the slope when the homes were originally built. Common sense suggests that if there are existing boulders at a construction site, they had to come from somewhere, at some point in time: you can’t fight gravity! There are hundreds of such locations around the state with structures at varying levels of risk.

In 2005 the Survey was asked by Douglas County to review the church’s development plans for a major expansion on the property. The church sits atop a bluff that is composed of hard, blocky Castle Rock Conglomerate overlying soft, erodible Dawson Arkose (a type of sandstone). Tension fractures in the cap rock conglomerate indicate that large blocks are actively detaching from the cliff face, and large fallen blocks are present on the slope below. Some of these large rocks had even been incorporated into the landscaping of homes below the bluff.

However, since the homes pre-date the proposed expansion, the church was required to make every effort to ensure that the expansion will not further destabilize the bluff. The Survey and Douglas County were concerned that the proposed expansion would impose construction-related disturbances and vibrations that could increase the rockfall hazard. Post-construction runoff from the planned large roof and pavement areas could result in increased infiltration and seepage, further destabilizing the precarious blocks along the cliff.

A rockfall mitigation plan was developed for the site. The mitigation plan included (1) constructing a rockfall catchment trench, (2) cable-lashing a large pillar, (3) scaling unstable rocks, and (4) using rock bolts with wire mesh and shotcrete to anchor the larger areas of unstable rocks. The mitigation was completed in September 2008.

Rockfall poses substantial risks for housing and development in Colorado, given the mountainous terrain. Residential areas and buildings situated near steep slopes or rocky outcrops are particularly vulnerable to falling rocks, which can lead to severe property damage and pose significant safety hazards. The unpredictability of rockfall events complicates land-use planning and construction, necessitating detailed geoengineering surveys and the implementation of protective measures such as rockfall barriers and retaining walls. Developers must also ensure ongoing maintenance and monitoring to mitigate these risks effectively. Balancing the aesthetic appeal of mountain living with the inherent dangers of rockfall is a critical challenge for sustainable development in Colorado. For more on rockfall issues around the state, see the original RockTalk: Rockfall in Colorado.